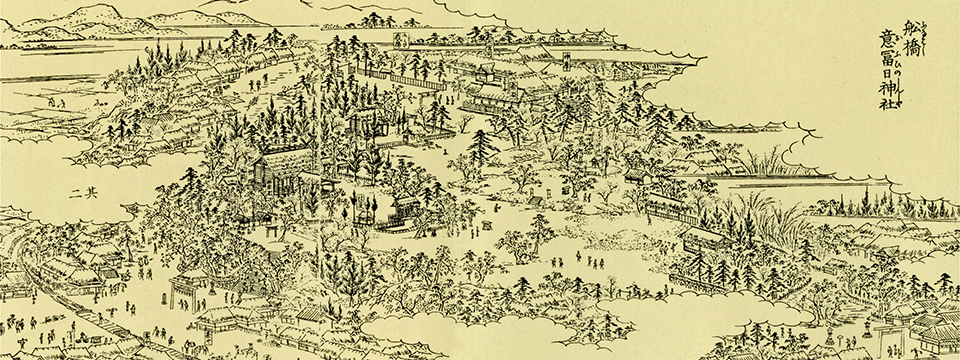

From Edo meisho zue

Japanese | English

About Oohi Jinja Shrine (Funabashi Daijingū Shrine)

Shikinaisha shrine, former Prefectural Shrine

Dedicated to Amaterasu-sume-ōmikami

Annual festival: October 20

History of Oohi Jinja Shrine (Funabashi Daijingū Shrine)

When Prince Yamato-takeru-no-mikoto went to pacify the eastern provinces in the fortieth year of the reign of Emperor Keikō (A.D. 110), he prayed here to Amaterasu-sume-ōmikami for success in his campaign, and for the people suffering from a drought, and there was a manifestation of divine favor. That was the beginning of this shrine.

The compilation of the Engishiki (Procedures of the Engi Era) was completed during the Heian period in 927, and this shrine is a shikinaisha shrine (a shrine listed in the Engishiki).

During the reign of Emperor Goreizei in the Tengi era (1053-1058), Minamoto no Yoriyoshi and his son Yoshiie repaired the shrine. During the reign of Emperor Konoe in the Ninpei era (1151-1154) the six villages of Funabashi were decreed as donations to the shrine, Minamoto no Yoshitomo rebuilt the shrine as a dedication, and the shrine was called in the document describing this Funabashi Ise Daijingū.

During the Kamakura period Nichiren (1222-1282) dedicated to the shrine a prayer for fasting so that the teachings of his school would prosper, along with a mandala and sword.

Around the beginning of the Edo Bakufu, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1546-1616) donated lands to the shrine and built a main sanctuary and subordinate shrine and other buildings in dedication. The shrine received a donation of land producing fifty koku of rice, which it held until the end of the Edo period.

In the Meiji period, each time Emperor Meiji (1852-1912) made an imperial visit to Narashino and Sanrizuka he sent an imperial envoy with an offering to the shrine.

The former appearance of the shrine can be known from the late Edo period Edo meisho zue (Famous Places of Edo Illustrated), but the shrine itself was burned down during the wars of the Meiji Restoration.

The main sanctuary was later rebuilt in 1873, and the hall of worship, subordinate shrine, gate, fence, and approach were rebuilt in 1923, 1963, 1975, and 1985, along with repairs to the Tōmyōdai (lamp tower) that is a Prefecture Designated Cultural Property.

The Etymology of Oohi

Oohi Jinja, also known as Funabashi Daijingū, is the oldest Shinto shrine in the Funabashi area. In its first appearance in historical records in the Nihon sandai jitsuroku(*1) in an article for 863, the words “Shimōsa-no-kuni Oohi-no-kami” appear. This is the oldest record pertaining to the area of Funabashi City. In the mid-Heian period major Shinto temples were listed in the Jinmyōchō(*2) (Register of Deities) of the Engishiki. Oohi Jinja was mentioned among the eleven shrines of Shimōsa Province, and was one of the few shikinaisha shrines in eastern Japan.

Regarding the etymology of Oohi and the nature of the kami, there is the theory that in ancient times the kami was a kami of food called Ōi. After World War II the theory that the kami was the tutelary kami of the ancient and powerful Oho clan was also put forth. The ancient reading of Oohi was Ohohi, and since the ancient Japanese writing system permitted the character for “sun” (日, hi) to be rendered phonetically as another character also read hi (比), “fire” (火, hi) as hi (肥), etc., and since historically Oohi Jinja has a deep connection with sun worship, it has been therefore suggested that the original meaning of Oohi was “great sun” or “great sun kami” (Mitsuhashi Takeshi, Oohishin kō, Thoughts on the Kami of Oohi). In other words, from medieval times until the end of the Edo period the kami popularly called Funabashi Shinmei and also the main kami of Oohi Jinja, Amaterasu-sume-ōmikami, were anciently both the major sun kami of this area. This is the leading theory at present.

Relationship with Ise Jingū Shrine

As mentioned above, since medieval times this shrine often seems to have been called Funabashi Shinmei. Shinmei means a shrine that is a separate enshrinement of Ise Jingū shrine.

Accordingly, it is thought that the kami of Oohi, who was the most powerful sun kami of the region in ancient times, was assimilated into Ise Jingū in the medieval period. The general outline can be hypothesized as follows. Near the end of the Heian period in 1138 the area centered around Natsumi became Mikuriya, the estate of Ise Jingū. In actuality the area gave tribute to Ise Jingū in the form of white cloth. From that relationship, Ise Jingū was separately enshrined in this area and a Shinmei-sha shrine was created. Needless to say, the highest sun kami Amaterasu-sume-ōmikami was enshrined here. Eventually the powerful local sun kami was merged with Shinmei-sha shrine as being the same kami, to become Funabashi Shinmei, or Funabashi Daijingū.

Who was Funabashi-dono?

In the old records of Kenjitsu-ji temple in Takomachi, in a document called Nichizon yuzurijō dated 1397 transferring the title to land, the term Funabashi-dono (Lord Funabashi) appears. It is not clear who this refers to, but in a later document titled Takagi Tanetoki kinsei (Funabashi monjo) from 1578, Funabashi-dono again appears referring to the high Shinto priest of Oohi Jinja. It is very likely that the former also referred to the high priest. It is hypothesized that in the early Muromachi period, the high priest of Oohi Jinja was also the resident lord of an estate, though a small one.

Changes in the Edo Period and After

The year after he moved to Edo in 1591, Tokugawa Ieyasu made donations to the major temples and shrines within his estates, and donated land producing fifty koku of rice to Funabashi Shinmei: farmland able to be worked by five wealthy farmers.

From that time until the end of the Edo period, the shrine maintained a relationship with the Tokugawa Shoguns. To the right of the main sanctuary, Tokiwa Jinja shrine was built honoring Ieyasu, Hidetada, and so on. In the mid-Edo period the shrine was called the “foremost in the Kanto area” leading to a dispute with Ise Jingū.

In any case, in the Edo period the shrine was the most famous site in the Funabashi area, and was typically visited by travelers on an excursion.

However, in 1868 just before the beginning of the Meiji period, the Boshin War spread to the Bōsō area and the shrine became a stronghold of deserted Bakufu troops. The shrine burned down by fires said to have been started by Imperial artillery attacks.

In the early Meiji period the shrine consisted of a temporary shrine, but was soon properly reconstructed. According to the early Meiji policies of the new government, when the ranks of the Shinto shrines throughout Japan were fixed, the shrine was designated as the only Prefectural Shrine in the current municipal area.

Cultural Treasures and Events

The Tōmyōdai (lamp tower) in the shrine precincts is a mixed Japanese-Western style building completed in 1880. It is the largest extant private lighthouse in Japan, and is a Chiba Prefecture Designated Cultural Property.

A festival is held on October 19 and 20. The amateur Sumo dedicated on the 20th is called “Funabashi Fighting Sumo” and is famous throughout the Kanto area.

Besides the annual festival (October 20), the Kagura music performed for the three days of the New Year, Setsubun, and the Ni-no-tori day of December is Funabashi City Designated Intangible Folk Cultural Property.

Notes

1. Nihon sandai jitsuroku is a historical record compiled at imperial command during the Heian Period. It covers the period from 858 to 887 and the reigns of the Emperors Seiwa, Yōzei, and Kōkō.

2. Jinmyōchō consists mainly of the ninth and tenth fascicles of the Engishiki, the detailed regulations under the mid-Heian ritsuryō system, listing the names of kami. It lists 2,861 shrines to which that the Imperial Court had made offerings of hōhei (hemp rope with paper streamers). It is an important source for knowing the influence of the shrines of that time.